Different Ways to Break Even Analysis

Andrei Mitskevich PhD in Economics, Associate Professor of the Higher School of Financial Management of the Academy of National Economy under the Government of the Russian Federation, Head of the Consulting Bureau of the Institute of Economic Strategies

Break even analysis

The company's management has to make various management decisions regarding, for example, the sale price of goods, sales volume planning, opening new outlets, increasing or, conversely, saving on certain types of expenses. In order to understand and evaluate the consequences of the decisions made, it is necessary to analyze the ratios of costs, volume and profit.

The break-even analysis shows what happens to the profit when the volume of production, price and basic cost parameters change. The English name for break-even analysis is CVP-analysis (cost - volume - profit, that is, “costs - output - profit”) or Break - even - point (break-even point, break-even point in this case).

Who doesn't know this? However, only a few use the classics in the life of firms. Why? Maybe "professional economics" is so out of touch with life? Let's try to understand what CVP analysis is and why its fate is ambiguous. At least in our country.

Assumptions made in the CVP analysis

Break-even analysis is carried out in the short run under the following conditions in a certain range of production volumes, called the acceptable range:

- costs and output in the first approximation are expressed by a linear relationship;

- productivity does not change within the considered changes in output;

- prices remain stable;

- stocks of finished goods are insignificant.

Academician and our only compatriot - Nobel Prize winner in economics for 1975 L.V. Kantorovich said: “Mathematical economists begin all their work with “suppose that...”. So this cannot be assumed.” Perhaps, in our case, the professors stepped on the same rake?

The answer to this question pleases: the hypotheses are working, tested by practice

management accounting. If they are violated, it is not difficult to make changes to the model.

The acceptable range of production volumes (relevance area) is determined by the cost linearity hypothesis. If the hypothesis is not in doubt, the range is accepted as the constraints of the CVP model. Basic classical ratios:

1. AVC ≈ const, i.e. average variable costs are relatively constant.

2. FC are unchanged, i.e. there is no threshold effect.

Then the total cost of producing a product is determined by the relation

TC \u003d FC + VC \u003d FC + a × Q, where Q is the volume of output.

A single-product task lives in textbooks, and a multi-product task lives in practice.

- Single-product tasks answer questions from the field of break-even analysis in the form of the amount of product produced ((2). Most often, CVP analysis in theory comes down to determining the classical break-even point, which shows how many units of production need to be produced to cover all fixed costs. How as a rule, it also applies to the target profit, i.e. it comes down to determining the volume of output that provides a given profit.

- Multi-product tasks answer the same questions in the form of revenue (TC). At the same time, its structure is assumed to be unchanged, at least in the sense of the constancy of the share of marginal profit in revenue.

Accounting methods affect the applicability of CVP analysis. Break-even analysis is carried out using Variable Costing, since Direct Costing and even more so Absorption Costing give errors. If a company does not use at least Direct Costing, then there will be a break-even analysis, therefore one of the reasons for the unpopularity of CVP analysis in Russia is the dominance of Absorption Costing.

Break even points

1) The classical break-even point in terms of the number of units of production assumes the payback of total costs (TC = TC). The critical value is considered to be such a value of sales at which the company has costs equal to the proceeds from the sale of all products (ie, where there is neither profit nor loss).

In a single-product variant, the value of the break-even point (Q b) is directly derived from this ratio:

This formula dominates the literature and, in fact, therefore, has earned the name of the classic break-even point (see Fig. 1).

Rice. 1. Classical CVP-analysis of the behavior of costs, profits and sales volume

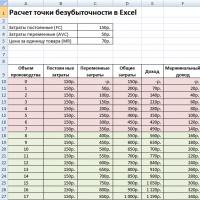

An example of calculating the classic break-even point by the number of units of production

The Corporation decides to open several "mini-wholesale" stores. Their characteristics:

- narrow specialization (office paper, mainly A4 format)

- small retail space (premises up to 20 sq.m., or a remote outlet);

- minimum sales staff (up to two people);

- form of sales - mostly small wholesale.

Table 1

- Marginal profit per unit of production: 224 -180 \u003d 44 rubles. We calculate the critical point using the formula:

- Break Even Point = Fixed Costs / Profit Margin Per Unit

We get: 10000: 44 = 227.27.To reach the critical point, the store needs to sell 228 reams of paper per month (10 reams per day), with six business days per week.

2) Multi-product break-even analysis. So far, we have assumed that there is one product, but in real life this is a minor special case. Paradoxically, the multicommodity case is less in demand in the literature and even more so in practice. The fact is that in this case the result of the break-even analysis is difficult to interpret. For a practitioner, it is not specific, since it gives hundreds of answers instead of a clear guideline for evaluation.

Let's consider the mathematics of this case. It is clear that the revenue must cover the total costs. In this case, we obtain not one break-even point, but a plane in the N-dimensional space, where N is the number of types of products. If we make a fairly correct and accepted in classical management accounting assumption about the constancy of AVC i = V i , we get a linear equation:

These points, by the logic of reasoning, are very similar to the points of the marginal I breakeven variable. Unfortunately, the remaining inseparable fixed costs cannot be distributed between products on the same and balanced bases. If all products are cash cows, such a base could be the notional contribution margin (revenue minus variable costs minus each product's own fixed costs). But since output is unknown in the break-even point question, neither the notional contribution margin nor the revenue work.

In the second step, you will have to allocate the remaining costs:

NFC = FC - ΣMFC i

Options:

a) equally, if there is no reason to prefer any one product;

b) in proportion to the planned revenue, if the sales plan is drawn up. Naturally, only the total fixed costs are shared;

c) if you have a plan, you can return to a balanced base (for example, marginal profit), but without part of the production

attributed to cover own costs (MPC i).

An example of calculating break-even points based on the developed Direct Costing.

Suppose a firm produces two types of products: "Alpha" and "Beta", sold at a price of 9 and 20 thousand dollars apiece, respectively. Average Variable Costs (AVC) are planned at $4,000 and $10,000 respectively.

Individual fixed costs for Alpha were $2,000,000 for the planned quarter, and for Beta, $8,000. The remaining fixed costs (NFC) turned out to be $10,000.

a) when dividing undivided fixed costs equally (5000 per type of product), we get:

Let's try to determine the break-even points in different ways. First, we calculate the coverage of our own fixed costs:

b) when dividing in proportion to the plan, you need to know this plan: 2900 and 2175, for example, in pieces. As the distribution base, we take the proceeds minus the coverage of own fixed costs:

22500 thousand dollars \u003d 2900 x 9 - 400 x 9 for Alpha;

$27,500 = 2175 x 20 - 800 x 20 for Beta.

c) the marginal profit base assumes that the planned output is reduced by the amount of own coverage (in units):

2900 — 400 = 2500 2175 — 800 = 1375

Conclusion: the deviations in the calculations are small, so you can use any of the proposed methods in the case of an approximate equality in the volumes of products. Otherwise, it's better to use methods B and C:

B - for growing markets and products;

B - for "cash cows".

3) The classical break-even point in terms of revenue is the most common approximate solution to a multi-product problem. It is assumed that the revenue structure changes insignificantly. The task is set as follows: to find such a value of revenue at which profit is zeroed. To do this, the economist requires a coefficient ( To), showing the share of variable costs in revenue. It is not difficult to find it, knowing the share of variable costs in total costs and profit in revenue. As a result, we get the equation:

For example:

- share of variable costs in revenue = 9742/16800 = 58%;

- fixed costs = 5816 thousand rubles;

- break-even point \u003d 5816 / (1-0.58) \u003d 13848 thousand rubles of revenue

In contrast to the classical break-even point in terms of the number of units of production, here it is necessary to make a reservation regarding the accuracy of the results:

- formula (7) is certainly correct with the same output structure;

- however, a less stringent condition can also be formulated: the invariance of the coefficient k, i.e. share of variable costs in revenue.

- Break-even point based on margin ordering in descending order. The break-even point shifts to the left when using the ordering of products in descending order of marginal profit.

Let's consider this interesting and rarely described effect with an example. So, the firm has fixed costs equal to $16,000 and produces 4 products with different shares of marginal profit in revenue (see Table 2).

Table 2. Initial data for calculating the break-even point based on marginal ordering

|

Product |

Revenue (TK) Doll. |

Marginal profit (/OT), USD |

Share of contribution margin in revenue |

|

Calculate the break-even point for revenue based on formula (7):

Let's determine it taking into account that we will first produce the most profitable products: A and B. They are just enough to cover fixed costs: μπ(A) + μπ(B) = 12000 + 4000 = 16000 = FС. Thus, we obtain an optimistic estimate of the break-even point:

20000 + 8000 = 28000.

The break-even point based on ascending margin order gives a pessimistic estimate. Let's use the same example to illustrate. Products D, C, B are only enough to cover $12,000, and the remaining fixed cost of $4,000 is one-third of the output of product A. That is, a pessimistic estimate of the break-even point:

Break-even points based on marginal descending and ascending ordering together give an interval of possible break-even points.

4) Point 1. LCC break even. The Life Cycle Costing approach to the problem of cost and profit defines the break-even point as an output that pays for the full costs, taking into account the entire life of the product. The LCC approach encroaches on the prerogatives of investment design. In addition to fixed costs, he also insists on covering investment costs.

An example of an LCC analysis

Let's say a consortium of Russian firms has invested $500 million in research and development (R&D) for a new aircraft.

Fixed costs are made up of $700 million in R&D (a one-off cost in a given year) plus an annual fixed cost of $50 million. Variable cost per aircraft - $10 million. It is expected that 25 aircraft will be produced per year, and they can be sold on the market for a maximum of $16 million. How many planes need to be sold to compensate for all costs without taking into account the time factor (this is also a break-even point, but taking into account what?) and how many years will it take?

Solution: Let's denote the unknown number of years as Y. Fixed costs will depend on the number of years to reach the break-even point: 700 + 50 x Y. Equate the total costs and revenue for Y years:

700 + 50 x Y + 25 x 10 x Y = 25 x 16 x Y.

Hence Y = 7 years, during which 175 aircraft will be produced and sold.

5) Marginal break-even point (payback point for an additional unit of output). In modern complex production, marginal costs (for producing an additional unit of output) do not immediately become lower than the price. Release,

providing break-even of an additional unit of production, is determined by the ratio:

Q bm: P \u003d MS (Q bm) (8)

This point shows the moment (output) when the company starts to work "in plus", i.e. when with the release of one more unit of production, profits begin to grow.

Unfortunately, there is no more detailed formula. This ratio

6) Break-even point of variable costs (point of coverage of variable costs):

TR = VC or P = AVC. (9)

It shows that the process of recoupment of fixed costs will soon begin. This is an important indicator both for managers who “started” a new product, and for owners. However, there is no more intelligible formula for calculations here either. The reason is the same: the ratio

(9) always individually.

Target profit points

They show the output of a single product (or revenue - in the case of multi-product production), providing a given mass or rate of return.

1. Target profit point by the number of units of production.

The traditional indicator is the output that provides the target profit. Similar calculations are performed in many firms. Suppose the required profit is π, that is,

This formula is easily modified in the case of a target after-tax profit. Here are the simplified calculations. If the target profit after tax should be equal to z, then (TR - TC) × (1 - t) = z, where t is the income tax rate. Therefore, (P - AVC) x Q x (1 - t) = z + FC × (1 - t) or

2. The target profit point for revenue is easily calculated by analogy with formula (7):

In the multicommodity case, it is subject to the same restrictions on the invariance of the coefficient k, i.e. share of variable costs in revenue.

Sensitivity analysis is based on the use of the “what happens if one or more factors that affect the amount of sales, costs or profits” change. Based on the analysis, you can get data about the final result with a given change in certain parameters. The sensitivity analysis is based on safety edges.

Safety edges (sometimes translated as safety margin or safety margin) show the margin of safety, break-even business as a percentage or natural units, or in rubles of revenue. The percentage representation is more visual and, most importantly, allows you to normalize this important indicator. Although these norms are extremely approximate, they are useful. Mathematicians speak of such figures and formulas with disdain: "management indicators." But this “engineering approach” cannot be avoided.

Classic safety edge by number of units:

It shows how much percentage revenue can decrease with break-even production. Less than 30% is a sign of high risk.

Classic Safety Edge by Revenue:

Both of these safety margins are good for the business as a whole, as fixed costs are understandable, but not very useful for business segments. However, the "frontal" application of variable or marginal costs, as you remember, requires the non-linearity of their functions. Classical management accounting does not study these functions and therefore is forced to consider them linear. Does this mean that there are no other safety edges than the classic ones? The answer will be negative.

The price safety margin shows how much price needs to be lowered in order for the profit to become zero. This will be at the critical price P k = AC. Then the margin of safety will be as a percentage of the existing price:

The variable cost safety margin shows how much the unit variable costs need to increase in order for the profit to go to zero. The critical value of AVC is reached at AVC = P - AFC. Because

The margin of safety for fixed costs in absolute terms is equal to profit, and in relative terms:

Please note that in formulas (15-17) the output remains unchanged.

Problems in determining break-even points

If a firm faces semi-fixed costs, there may be multiple break-even points. The break-even chart (see Figure 2) shows three break-even points, and profit and loss zones follow each other as the volume of activity increases.

Rice. 2. Multiplicity of classical break-even points in the case of semi-fixed costs.

Similar reproduction also applies to non-classical break-even points.

Difficulties in conducting a break-even analysis may be due to the following reasons:

- if supply is high, the unit price may have to be lowered. Consequently, a new break-even point will appear, lying to the right;

- "Large" buyers are likely to be eligible for volume discounts. The break-even point shifts to the right again;

- if demand exceeds supply, it may be appropriate to increase the price. This will move the break-even point to the left;

- the cost of raw materials and materials per unit of production may decrease with large volumes of purchases or increase with supply interruptions;

- the unit cost of wages of production workers is likely to decrease with a large volume of production;

- both fixed and variable costs tend to increase over time;

- costs can not always be accurately divided into fixed and variable;

- the structure of sales can change quite significantly.

Primitive business plans simply ignore all these elementary analytical calculations.

However, it is believed that break-even analysis is carried out everywhere and its value is great. My observations do not support this. Like any model, the CVP has its own “battlefield”, and it is fragmented. Many firms conduct CVP analysis only for new projects. Unfortunately, regular work with the profitability of products and segments in our country is still not enough.

Case with solutions

So, two firms: CJSC "Staromehanicheskij Zavod" (hereinafter - SMZ) and OJSC "Foreign Automation" (hereinafter - ZAM) work in the Little Russian market and manufacture a part used in car repairs. Today, these two companies have divided the Russian market - each holds 50%. Manufactured parts have the same quality and price. The production facilities of both companies are located in the vicinity of Mariupol.

However, companies differ radically in their cost structure. "Foreign Automation" has a fully automated and very capital-intensive production. And the "Old Mechanical Plant" is a non-automated production with a large share of manual labor. Monthly profit and loss statements of companies are as follows (see table 1).

Table 1. Initial situation (in c.u.)

|

Indicators |

"Foreign Automation" |

"Old Mechanical Plant" |

|

Sales, pcs. | ||

|

Price for one | ||

|

Unit Variable Costs | ||

|

Unit fixed costs | ||

|

Total unit cost | ||

|

Full costs |

9.5x5000 = 47500 |

9.5x5000 = 47500 |

|

50000 — 47500 = 2500 |

50000 — 47500 = 2500 |

Both companies are looking at ways to increase profits. One is to start selling your products to a sizable but relatively low-income (or frugal) segment of customers who are currently not being served. The potential capacity of this segment is 2000 pieces per month. Thus, the company that has captured this segment, sales in physical terms will increase by 40%. The only problem is that in this segment, consumers will buy parts at a price no higher than 8.50 USD. e. per piece, i.e. 15% lower than the market price and 1 c.u. That is, below the total cost of production at the moment. How can you sell below cost? - the head of the FEO with many years of experience at the "Old Mechanical Plant" is indignant.

Question 1: Let's say both companies can cost-free segment the market (i.e. start selling parts to the economy segment at a 15% discount without undermining their full-price sales to wealthy customers). To what extent can each company increase profits if it increases sales (in units): a) by 20%, that is, by capturing half of the economy segment?

b) by 40%, capturing the entire economy segment?

Should companies (one or both) use this opportunity to increase profits?

|

Question |

Response Logic |

"Foreign Automation" |

"Old Mechanical Plant" |

|

Profit increment (Δπ) is calculated through the marginal profit per unit of production in an additional batch (αμπ) |

αμπ \u003d 8.5 - 2.5 \u003d 6 Δπ \u003d 6x1000 \u003d 6000 |

αμπ \u003d 8.5 - 5.5 \u003d 3 Δπ \u003d 3x1000 \u003d 3000 |

|

|

αμπ \u003d 8.5 - 2.5 \u003d 6 Δπ \u003d 6x 2000 \u003d 12000 |

αμπ \u003d 8.5 - 5.5 \u003d 3 Δπ \u003d 3x2000 \u003d 6000 |

||

Conclusion: Both companies will be happy to "grab" even half of the economy segment, not to mention the happiness of taking possession of it entirely.

Question 2: What to do if neither SMZ nor ZAM can effectively segment the market, and both firms will be forced to set a single price for all buyers (i.e. 8.50 USD for both the economy segment and wealthy buyers ).

A. Calculate the BOP (break even sales volume) for each

companies, if the price is reduced to 8.50 c.u. e.

b. How much would each company's profits increase if its sales

increase by 40% (in pieces)?

Attention: BOP (break-even sales volume) in this case assumes that the company should receive the same, not zero, profits.

Breakeven sales volume is more common in practice than the classic CVP analysis. In life, it is found, in textbooks - not always. This is a variant of the target profit point in dynamics: when factors change, the profit remains at the same level. The break-even volume of sales assumes that the company should receive the same profits during changes, and not zero. For example, an old machine has been replaced with a more efficient and expensive one. Naturally, the question arises, how much should output be increased in order to “recoup costs”?

|

Question |

Response Logic |

"Foreign Automation" |

"Old Mechanical Plant" |

|

|

Calculated through the equality of marginal profits before and after changes |

μπ (up to) \u003d 7.5x5000 \u003d 37500 \u003d μπ (after) = 6xQ μπ (after) = 7.5x5000 =37500 |

μπ (up to) \u003d 4.5x5000 \u003d 22500 \u003d μπ (after) = 3xQ |

||

|

b. Output growth by 40% |

Profit growth (Δπ) is calculated as the difference between marginal profits before and after changes |

μπ (after) \u003d 6x7000 \u003d 42000 μπ \u003d 42000 - 37500 \u003d 4500 |

μπ (after) = 4.5x5000 = 22500 |

|

This is what we call cost structure competitiveness with lower average variable costs. Foreign Automation will survive the price cuts, but Old Mechanical Plant will not. Dumping (the game to lower prices) is the lot of firms with low variable costs. There are no fixed costs here.

Question 3: While the companies were thinking, their market was invaded by a strong competitor - "Avtomobilny Zavod". He easily captured half the market, trading the same parts for $9. We will have to return to the original situation and analyze the reliability of the SMZ and ZAM. Both firms lost half of their sales (in units). The results are presented in table. 2.

Table 2. The situation after the invasion of the "adversary" (in c.u.)

|

Indicators |

"Foreign Automation" |

"Old Mechanical Plant" |

|

Sales, pcs. | ||

|

Price per piece e. | ||

|

Specific | ||

|

variables | ||

|

costs | ||

|

Fixed costs (per month) | ||

|

Specific | ||

|

permanent |

14 = 35000: 2500 | |

|

costs | ||

|

Total unit cost | ||

|

Full costs |

16.5x2500 = 41250 |

13.5x2500 = 33750 |

|

22500 — 41250 = -18750 |

22500 — 33750 = -11250 |

Of course, both companies are at a loss, but it is perhaps easier to transfer them to the Staromehanicheskoy Zavod. This is what we call cost structure reliability with lower fixed costs.

Question 4: Morning. The invasion of the "Automobile Factory" turned out to be a nightmare. Given that no single company can segment the market, what advice would you give each company on this opportunity?

Answer: "Foreign Automation" should lower the price, but "Old Mechanical Plant" - no. ZAM has every chance to win price competition due to lower variable costs.

After analyzing the situation, ZAM decided to take the opportunity to sell parts to a new segment and reduced prices by 15%. Its sales rose to 7,000 units per month at a price of $8.50. e. Belatedly, SMZ was also forced to cut prices to keep its customers. SMZ management believes that if they had not reduced their prices, they would have lost 60% of sales. Unfortunately, after the price reduction, SMZ operates at a loss.

Question 5: Was Staromekhanichesky Zavod's decision to cut prices financially sound? For example, if SMZ decides to leave this market entirely, it can cut its fixed costs in half. For example, refuse to rent premises, land and other expenses. The remaining 50% of fixed costs is servicing a bank loan for the purchase of equipment that has a zero salvage value. Calculate and compare profits for different options.

Position after price reduction:

μπ (up to) \u003d 4.5x5000 \u003d 22500

μπ (after) = 3x5000 = 15000

FC = 20000, π = -5000.

Alternative option: do not reduce the price, but lose part of the market:

μπ (up to) \u003d 4.5x5000 \u003d 22500

μπ (after) \u003d 4.5x2000 \u003d 9000

FC = 20000, π = -11000.

Therefore, price reduction is beneficial in the short run.

When leaving the market, π = -10000. Therefore, one should stay and reduce the price, although production will be unprofitable: FC = 20000, π = 15000 - 20000 = -5000.

Fortunately, the managers of the Old Machine Factory read Michael Porter's book Competitive Advantage and decided to analyze how the entire value chain works. As a result of market analysis, they found that at least 3,500 parts are bought monthly by drivers, who then have to remake this part themselves so that it better suits their brand of car: namely, the Volga. Thus, there is an opportunity on the market to produce a specialized version of the part for this category of drivers. And although the cost of production at the LMP will increase, the additional costs will still be less than what drivers currently spend on reworking the part.

For the production of specialized parts, SMZ will have to invest additional capital, the fee for which will be 3000 c.u. per month.

Question #6: In order to produce specialized parts, SMZ would have to buy new equipment and a new building, which would cost $23,000. fixed costs per month instead of 20,000 c.u. e. per month. The plant management is convinced that they will be able to sell specialized parts for 6 cu more than conventional parts (ie 16 cu), but the unit variable costs will increase by 3.00 cu. e. per month. Would it be beneficial for SMZ to focus on the production of only specialized parts?

Answer: FC \u003d 23000, π \u003d (1b-8.5) x3500 - 23000 \u003d 3250. Yes, the manufacture of only specialized parts is profitable, since the profit will increase by 3250 - 2500 \u003d 750 c.u. e.

Question #7: What is the minimum number of custom parts that SMZ must sell per month to exceed the profits it currently earns as a generic parts manufacturer? Remember? This is what we call break-even sales volume.

Answer: FC \u003d 23000, π \u003d (16-8.5) xQ - 23000 \u003d 2500. Q \u003d 3400.

Question No. 8: How much will Staromekhanichesky Zavod's profits increase as a manufacturer of specialized parts if it sells 3,500 pieces per month at a price of 16 USD per piece. ?

Answer: 3250 — 2500 = 750.

"Unfamiliar options for break-even analysis"

There are other options for break-even analysis. For most, they will be unexpected. We call them "three break-even points":

The first and fastest achievable - the marginal break-even point - shows at what output the price will begin to recoup the additional costs of producing one more unit of output (P > MC - in conditions of perfect competition or MR > MC - in conditions of imperfect competition). The first condition (P > MC) corresponds to the spirit of management accounting and is quite worthy to use. The second (MR > MC) is suitable only for pure economic theory, although it would be presumptuous to deny the possibility of its practical use.

The second point - the break-even point of variable costs - shows the output at which it will be possible to cover all variable costs (TR\u003e VC). Naturally, such a statement of the problem is typical for Variable Costing. In the case of using Direct Costing, a similar point will be called the break-even point of direct costs (TR> DC).

The third point - classical - sets the output at which it will be possible to cover all costs (TR\u003e TC). It has filled all the textbooks, so most students and professionals think that the classic break-even point is CVP analysis. This is a clear exaggeration, or rather an underestimation of the role and capabilities of CVP analysis.

Example. Evaluation of the work of company stores and allocation of general administrative costs

At the beginning of the year, a large Moscow company set an ambitious goal: to open 200 new branded stores across the country in a couple of years. The central office economist asked how to allocate the costs of the central office between stores? The answer, surprisingly, relies on the “three break-even points”:

1. A newly opened store must first recoup its current upkeep. This is the first and concrete task for management. It is not necessary to post costs to such stores. This is also a marginal break-even point, but not for products, but for stores. Ceteris paribus, the team that gets through the first stage faster will “win the capitalist competition.” Moral incentives have not been canceled.

2. As soon as the store contributes to the coverage, another stage of development will begin. Here it is required to recoup the accumulated current losses of the previous stage. This is also a kind of break-even point for variable costs, but not for products, but for stores.

3. Only at the next, third stage, it is necessary to fight for the classic payback. And only here you can distribute the costs of the central office between stores. Advanced Direct Costing welcomes this solution, but does not provide advice on which overhead cost bases to use.

It is on such a decision that the business plan of each store or branch, representative office, business area, and so on should be aimed.

Ready-made business plan with calculations using the example of a web studio

Ready-made business plan with calculations using the example of a web studio Registration of an internal memorandum: sample document and drafting rules

Registration of an internal memorandum: sample document and drafting rules Break even. Formula. Example of model calculation in Excel. Advantages and disadvantages

Break even. Formula. Example of model calculation in Excel. Advantages and disadvantages Advance report is ... Advance report: sample filling

Advance report is ... Advance report: sample filling How to stitch documents with threads by hand?

How to stitch documents with threads by hand? Disciplinary sanction for non-fulfillment of official duties

Disciplinary sanction for non-fulfillment of official duties Binding your book

Binding your book