On the history of trade in Soviet times. Trade in the ussr. Consumption benchmark

Store shelves full of the same type of goods, the gloomy faces of saleswomen, gigantic queues for any scarce goods - in such conditions Soviet people were shopping for many decades. A trip to the store in the USSR turned into a special life with its own rules, concepts and phraseological units. The goods were “taken out”, they were “thrown away”, the queues were “alive”, “storehouses” of the products purchased for future use were created at home. The deficit - and they could have anything, from smoked sausage to furniture sets - were received "by pull", "from the back door," sometimes paying for something useless. True, there were also ideal stores, but only in the form of a closed system of special distributors or currency departments.

Only in the first years of its existence, trade in the Soviet Union was based on market principles. But, once embarking on the path of a planned economy, it has forever remained, in fact, a distribution system.

Soviet trade in Estonia did not leave such a depressing impression as in the hinterland of Russia. Modern shopping center In Soviet times, "Silhouette" in Narva was the largest shopping complex in the city (of course, not counting the city market) and was mainly focused entirely on women. The dream of every graduate of the Narva trade school was to work as a seller in this particular store.

1959 year. Product department. Typical. If my vision does not fail me, the products on the counter are not very rich, to use euphemisms. And to put it bluntly and without embellishment, the counter is completely empty. True, it should be admitted that there is something hanging behind the seller's back. To be honest, I did not understand what it was. Tolley decayed meat carcasses, or something wrapped in oiled paper. Okay, let's assume that this is meat.

1964 Moscow. GUM. Gum ice cream has always been popular. And in 64th ...

And in 1980 ...

And in 1987.

But, as they say, ice cream is not the only one ...

1965 year. In Soviet times, the approach to design was very simple. There weren't a bunch of stupid names. Stores in all cities were called simply, but understandably: "Bread", "Milk", "Meat", "Fish". In this case, it is the “Grocery store”.

And here is the toy department. The store, therefore, is a manufactured goods store. All the same 1965. I remember that in 1987 a girl I know, a saleswoman in the Dom Knigi store on Kalininsky, told me that she was always uncomfortable when foreigners froze in stunned silence, watching her calculate the cost of a purchase on the accounts. But that was 1987, and in 1965 no one was surprised by the accounts. The sports department is visible in the background. There are different kinds of chess, checkers, dominoes - a typical set. Well, bingo and games with dice and chips (some were very interesting). In the foreground is a child's rocking horse. I didn't have one.

All the same 1965. Selling apples on the street. Please pay attention to the packaging - a paper bag (the woman in the foreground is putting apples in it). Such packages of third-rate paper were all the way one of the most common types of Soviet packaging.

1966 year. Supermarket - Self-service department store. At the exit with purchases, it is not the cashier with the cash register who sits, but the saleswoman with the invoices. The check was strung on a special awl (stands in front of the accounts). On the shelves there is a typical set: something in packs (tea? Tobacco? Dry jelly?), Then cognac and some bottles in general, and on the horizon are traditional Soviet pyramids of canned fish.

1968 year. Progress is evident. Instead of an account, there are cash registers. There are shopping baskets - by the way, quite so nice design. In the lower left row, you can see a customer's hand with a carton of milk - such characteristic pyramids. In Moscow, these were of two types: red (25 kopecks) and blue (16 kopecks). They were distinguished by their fat content. On the shelves, as far as you can tell, there are traditional cans and bottles of sunflower oil (sort of). Interestingly, there are two sellers at the exit: the one checking the purchases and the cashier (her head peeks out from behind the right shoulder of the aunt-seller with a facial expression typical of a Soviet seller).

1972 year. Let's take a closer look at what was on the shelves. Sprats (by the way, later they became scarce), bottles of sunflower oil, some other canned fish, on the right - something like cans of condensed milk. There are a lot of cans. But there are very few names. Several types of canned fish, two types of milk, butter, leavened wort, what else?

1966 year. Something I did not understand what exactly the buyers were looking at.

1967 year. This is not Lenin's room. This is a section for the House of Books on Kalininsky. Today these retail space jam-packed with all kinds of books (on history, philosophy), and then - portraits of Lenin and the Politburo.

1967 year. For children - plastic astronauts. Very affordable - only 70 kopecks apiece.

1974 year. Typical grocery store. Again: a pyramid of canned fish, bottles of champagne, a battery of green peas "Globus" (Hungarian, I think, or Bulgarian - I don't remember something already). Half-liter cans with something like grated beets or horseradish with beets, packs of cigarettes, a bottle of Armenian brandy. On the right (behind the scales) are empty flasks for selling juice. The juice was usually: tomato (10 kopecks a glass), plum (12 or 15, I don't remember already), apple (the same), grape (similar). Sometimes in Moscow there was a tangerine and an orange one (50 kopecks - wildly expensive). Next to such flasks there was always a saucer with salt, which could be added to your glass of tomato juice with a spoon (taken from a glass of water) and stirred. I've always loved to have a glass of tomato juice.

1975 year. City Mirniy. On the left, as far as you can tell, the deposits of bagels, gingerbread and cookies - all in plastic bags. On the right are eternal canned fish and - at the bottom - 3-liter cans of canned cucumbers.

1975 year. City Mirniy. General form store interior.

1979 year. Moscow. People are waiting for the end of their lunch break at the store. The showcase is decorated with a typical pictogram of the "Vegetables-Fruits" store. In the showcase itself, there are jars of jam. And, it seems, of one kind.

1980 year. Novosibirsk. General view of the supermarket. In the foreground are batteries of milk bottles. Further, in the metal mesh containers, there is something like canned fish deposits. In the background groceries - bags of flour and noodles. The general dull landscape is somewhat enlivened by plastic pictograms of departments. We must pay tribute to the designers there - the pictograms are quite understandable. Not like Microsoft Word icons.

1980 year. Novosibirsk. Manufactured goods. Furniture in the form of sofas and wardrobes. Further, the sports department (checkers, inflatable lifebuoys, billiards, dumbbells and various other trifles). Further down the stairs, there are televisions. In the background are partially empty shelves.

View of the same store from the side of the household electrical appliances department. In the sports department we can distinguish between life jackets and hockey helmets. In general, it was probably one of the best shops Novosibirsk (so it seems to me).

1980 year. Vegetable department. The line is watching the saleswoman tensely. In the foreground are green cucumbers, which appeared in stores in early spring (and then disappeared).

1980 year. Sausage. Krakowskaya, it must be.

1981 year. Moscow. Typical store design. "Milk". On the right, a woman is rolling a wildly scarce imported stroller with "windows".

1982 year. In the market, the Soviet people rested with their souls.

1983 year. Queue for shoes. Not otherwise, the imported boots were "thrown out".

1987 year. Queue for something.

Kvass saleswoman. People went for kvass with aluminum cans or three-liter cans.

1987 year. Electrical goods.

No comments.

Soviet underwear as it is. Without any colorful bourgeois packaging.

For especially spiritual people fashion footwear need not. But the women in this photo don't look very cheerful.

Shoes too ... But where to go? There is no other.

An almost sacred place is the meat department. "Communism is when every Soviet person will have a familiar butcher" (from a movie).

"Pork" - 1 ruble 90 kopecks per kilogram. Grandmothers can't believe their eyes. "Butcher, bitch, sold all the meat on the left!"

Soviet turn. What a tense look of people - "is it enough?"

“The meat will be brought in now. You will see, they will definitely bring him. "

"Eat meat!" Local brawl over the best piece.

Phallic symbol. It is enough to look at how reverently the aunt holds this object to understand that in the USSR sausage was much more than just a food product.

It is necessary to cut into more pieces of sausage, which will then be instantly swept off the counter.

Frozen hake is certainly not a sausage, but you can also eat it. Although, of course, all this does not look very aesthetically pleasing.

Not a single sausage ... For a Soviet color TV, a Soviet person had to pay almost a salary for 4-6 months ("Electronics" costs 755 rubles).

Vegetable department. In the foreground is a cart with some kind of rot. Moreover, it was assumed that someone could buy this rot.

An ineradicable antagonism between Soviet buyers and Soviet sellers. It is read in the man's eyes that he would gladly strangle the saleswoman. But it is not so easy to strangle such a saleswoman - the Soviet trade tempered people. Soviet saleswomen knew how to deal with buyers. More than once I saw a flurry of indignation and attempts to riot in lines, but the result was always the same - the victory remained with such aunt-saleswoman.

One of the features of the Sovok was the presence of a sophisticated system of benefits (all sorts of veterans, "prisoners of concentration camps", etc.). Various beneficiaries with red crusts in Soviet lines were hated almost as much as saleswomen. Look what a snout in a hat - not to "like everyone else" to take the put duck, he sticks a red crust - apparently pretends to be two ducks.

This photo is interesting not so much for the hake sold as for the packaging. Almost all purchases were wrapped in this brown tough paper in the USSR. In general, the darkest thing that happened in Soviet trade was packaging, which, in fact, did not exist.

Another queue.

And further…

And further…

Suffering. No comments.

Those who did not have time were late. Now spells won't help.

Queue to the dairy department.

"Our work is simple ..."

The line to the wine department.

1991 year. Well, this is already the apotheosis. Finita ...

And this is a completely different line, the line of people who dreamed of escaping from the Sovok at least for an hour. And no spirituality.

Is it true that in the Soviet Union in every store there were barrels of black caviar and it cost a penny? What was difficult to get? Were there queues? Was it possible to get normal food without cronyism? Is it true that the bread tasted better?

I remember almost nothing from the Soviet era, I was too young and my parents did not take me to the shops. From the 90s I only remember that I had to walk through the woods to the Moscow Ring Road for some bananas. Why I had to go after them, I still don’t understand, no one ate them anyway. I also remember on Tverskaya there was a very cool SweetSweetVay store, where they sold foreign sweets by weight. Now at this place is the Etazh cafe (by the way, the dump is awful).

At the shop window of the TSUM shoe department, 1934.

Showcase, 1939.

Metropol Bookstore, 1939.

Showcase of the Eliseevsky grocery store, 1947.

At a tobacco display case on Gorky Street, 1947.

At the window of the bookstore "Moscow"

At a showcase with oriental souvenirs, 1947.

1951 year. Moscow, Taganskaya square. Shop

Kutuzovsky prospect, house 18 - showcase with dishes. 1958 year. From the moment of its construction, the residential building with shops on the ground floor was popularly called "Pink Department Store". It was the first building to outline the line of the future Kutuzovsky Prospect to Novoarbatsky Bridge. Before its construction, the Mozhaisk highway smoothly turned into Dorogomilovskaya street, and it was completely incomprehensible why the house was being built at a strange angle to the existing streets. After opening, Pink Department Store was the most popular store in the area, with everything from coats to needles. Well, the dishes too.

In the same place, showcase with TV sets

St. Gorky. Radio goods store. 1960

St. Gorky. Shop window "Diet Products"

Shop "Ether".

Shop "Cheese"

St. Gorky. Showcase of the store "Russian Wines"

Showcase of the House of Toys on Kutuzovsky Prospect, 1960.

Department store Moscow, 1963.

Showcase and counters of the Moscow department store in the 70s.

Begovaya Street, 1969.

Gorky street. Moscow showcases. Shop "Men's Fashion", 1970.

Grocery store "Novoarbatsky"

On Malaya Gruzinskaya, 29. In V.S. Vysotsky's favorite store

Toy House, 1975

Orbita store

Voentorg on Kalinin Avenue, 1979.

TSUM GUT MO

GUM

GUM. Showcase of a grocery store. 1984 year.

Vostochny settlement. Store. 1985 year.

Department store "Detsky Mir". 1986 year.

House of Pedagogical Books on Pushkinskaya. 1986 year.

Directions of the Art Theater (Kamergersky per.), 1986.

Showcase on Arbat

Shop "Melody", 1989.

Department store "Moskovsky"

Do not sell, but give away

After the Civil War, the leadership of the young country decided to resort to the help of private traders in supply matters, and it was right.

The New Economic Policy, announced in the fall of 1921, allowed private trade along with state and cooperative trade. And already in 1922-1923, the share of private trade in retail turnover reached 75.3%. Thanks to this, the problem of providing the population with essential products was solved in a short time.

However, in December 1925, the Kremlin began to industrialize the country, for which it needed currency - to buy high-tech equipment. Prices for raw materials - the main item of Soviet exports - then fell due to the crisis. The export of agricultural products could help, but the peasants did not want to hand them over to the state at low prices, but tried to sell them to private owners with greater profit.

In December 1925, the Kremlin began to industrialize the country, for which it needed currency - to buy high-tech equipment

And the Kremlin followed the path of repression - the peasants were dispossessed and massively driven into collective farms, and private traders were removed from the supply sphere, making it centralized.

Such actions immediately led to a crisis. Groceries disappeared from the shops, for which huge queues with fights and pogroms lined up. Local authorities began introducing rationed sales of goods to curb wild demand, but this did not help. Bread cards appeared - they were first introduced in Odessa in the second quarter of 1928. In the same year, bread cards came to Kiev, Dnepropetrovsk, Kherson, Mariupol, and at the beginning of 1929 - to Kharkov. At the same time, due to a shortage of grain, the state stopped selling flour to the population. Outbreaks of famine began throughout the Union, including in Ukraine.

The situation in industry was aggravated - half-starved workers went on strike, which threatened to disrupt industrialization plans. As a result, the whole country followed the path beaten by the Odessa citizens: on February 14, 1929, the Politburo of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks approved a decree on the all-Union rationing system for distributing grain.

In Moscow and Leningrad, as the Russian historian Elena Osokina notes in her book Behind the facade of "Stalinist abundance", workers were entitled to 900 g of bread a day, their families and other workers - 500 g, and the proletariat of other cities of the Union - 300-600 g. day. The peasants were not given cards.

The workers were supposed to have 900 g of bread a day, their family members and the rest of the workers - 500 g, and the proletariat of other cities of the Union - 300-600 g per day. The peasants were not given cards.

In January 1931, cards were introduced for basic food and non-food products... At the same time, the population (in terms of importance for the cause of industrialization) was divided into four lists - a special, first, second and third. The first two hit the workers strategic enterprises Moscow, Leningrad, Donbass and other industrial regions. In the second and third - workers and employees of non-industrial cities and factories and factories that produced consumer goods. The peasants were again left behind.

The richest in those years were the top party officials, who received the so-called letter rations, which included all the basic foodstuffs.

Thus, by the 1930s, trade in the USSR had turned into the distribution of goods: each category of the population had access to its own types of distributors.

By market laws only commercial shops and collective farm markets worked, where prices were several times higher than state ones. Another category of outlets where goods could be bought, and not received with a card, was a network of currency traders. Initially, they were oriented towards foreigners, but in the fall of 1931 they were also opened for Soviet citizens, who could shop there by handing over gold, silver or antiques. It was Torgsin that helped many peasants survive in the hungry years 1932-1933: more than 80% of the goods sold through this network at that time were food, of which 60% were bread.

By the 1930s, trade in the USSR had turned into the distribution of goods: each category of the population had access to its own types of distributors.

The cards were briefly canceled only at the beginning of 1936, but trade remained rationed all the time. New crisis began in 1939 with the beginning of the war against Poland, and then Finland. In cities where the supply was better, huge queues of locals and visitors gathered, with whom they tried to fight with the help of the police.

“The question of clothing in Kiev is extremely difficult,” a certain Kievite NS Kovalev noted in a letter to the head of the Council of People's Commissars Vyacheslav Molotov at the end of 1939. - Thousands of queues to the shops gather for the manufactory and ready-made clothes since the evening. The police line up somewhere a block away in an alley, and then the “lucky ones” of five or ten people in single file, one after the other in a hug (so that no one skips out of line), surrounded by policemen, like prisoners, lead to the store. In these conditions, terrible speculation flourishes. "

In July 1941, with the beginning of the war, the rationing system was reintroduced in the USSR, which was liquidated only at the end of 1947. But for many years, some of the goods were actually distributed. For example, as Vitaly Kovalinsky, a Kiev historian, says, in the 1950s, flour was sold to the population according to lists, and only three times a year - on New Year, on May 1st and November 7th, the anniversary of the October coup.

Consumption benchmark

Things began to change in better side in the late 1950s. At this point, the Kremlin decided to focus on the development of food and light industry... As a result, the assortment in stores began to change qualitatively, where other products began to crowd out bread as the basis of nutrition.

“The share of bread and bakery products in the retail turnover of the country in 1940 it was 17.2%, in 1950 it was already 12.6%, and now it is about 6%, ”wrote the Soviet Trade magazine in April 1960.

In August of the same year, a decree was issued on the improvement of trade, after which wholesale fairs began to be held in the country, where enterprises showed samples of goods to representatives of trade organizations, and they, in turn, decided who to buy from whom. The specter of market relations loomed over the country, but it did not fundamentally change the situation.

Shops, says Nina Goloshubova, a professor at the Kiev National University of Trade and Economics, were rigidly attached to a specific supplier.

Prior to that, the resources of the republics were distributed by the State Planning Committee of the USSR. Shops, says Nina Goloshubova, a professor at the Kiev National University of Trade and Economics, were rigidly attached to a specific supplier. This gave rise not only to a shortage, but also to the monotony of goods on the shelves, which stale, because the industry produced products in very large batches, not in any way focusing on demand.

However, the innovation only slightly eased the situation. And it did not at all solve the problem of marriage, which was all-pervading in the Union: in a planned economy, manufacturers had guaranteed sales, and they did not care too much about quality.

“The state supervision authorities in the USSR Gosstandart system checked 1,788 enterprises of the Ministry of Light Industry in 1973 and found that 60% of them were producing products in violation of standards,” wrote Soviet trade in January 1975. “The supply of 364 types of products to the retail network was prohibited.”

Government initiatives did not save the stores from another feature - the massive "stuffing" of goods. They happened, as a rule, at the end of the month and were the echo of attempts by enterprises to fulfill their monthly, quarterly and annual plans.

Soviet buyers quickly adapted to these subtleties. For example, in Kiev, in the courtyard of the Ukraine department store, a crowd often gathered by the end of the month, expecting a “throw-in”. The place of collection was not accidental: the people of Kiev knew about another feature of the shops' work - their management, in order not to create long lines in the sales areas, sometimes ordered to sell the deficit right in the yard, at the place of unloading.

The top of the consumption pyramid

As early as the 1930s, a class of “special” buyers emerged in the USSR, which existed until the very end of the Soviet system. We could talk about different categories of the population - the military, pensioners, the poor, who were allocated and sold goods that were inaccessible to other citizens. But the real caste of privileged clients has become the party and economic nomenclature.

For the elite, everything was special: special sovkhozes grew food, special shops produced other products, then all this was supplied to special stores or special dining rooms, in which special buyers had the right to purchase all this at special prices (very loyal to wallets). The infrastructure was very extensive, it could cover almost all needs, up to sewing clothes.

“There was an atelier opposite the bank [of the current National Bank],” recalls the daughter of one of the workers of the Council of Ministers of the Ukrainian SSR on condition of anonymity. “There really were good craftsmen, but not everyone was allowed to sew clothes there.”

Since the 1930s, a class of “special” buyers emerged in the USSR, which existed until the very end of the Soviet system.

The entire special system worked in conditions similar to underground: the Soviet leadership did not really want to irritate its people. However, this was Openel's secret. Moreover, ordinary citizens have even learned to use inaccessible benefits.

For example, in the central part of Kiev there were many grocery stores with special departments. Thanks to them in open sale from time to time, scarce goods came in, lying on the shelves of distributors. The people even began to call such outlets "leftover shops", and it was here that the people of Kiev hunted for what was not available in the general trade network.

In addition to the elite, people who worked under a contract abroad joined in the sweet life. They received their salaries in foreign currency checks and could buy them in specialty store chains such as Kashtan, which sold inexpensive Soviet deficits and imported products.

“We mainly went there to buy shoes,” says Valentina Aleksandrova, the daughter of a specialist who worked abroad. “Because we had a lot of shoes in our stores, but they were of poor quality and ugly.”

System crash

This entire multi-level distribution system has led to the emergence of a super-elite class of merchants - directors and salespeople, and not only special, but also ordinary stores, chiefs of bases, warehouses, and other suppliers. They became heroes of folklore and the object of close attention of the employees of the departments for combating the theft of socialist property as delinquents who make money off the shortage, selling from under the counter. But in the conditions of the planned system, it turned out to be impossible to overcome this problem.

Meanwhile, it was not crooks and speculators who ruined Soviet trade, but the general problems of the state, which got involved in the Afghan war, faced a drop in oil prices and was unable to meet the needs of the population by spending money on the defense industry.

It was not crooks and speculators who ruined Soviet trade, but the general problems of the state, which got involved in the Afghan war, faced a drop in oil prices and was unable to meet the needs of the population, spending money on the defense industry

As a result, from the second half of the 1980s, the trade situation began to deteriorate. "Shopping trips are becoming more and more useless, as almost every day promises us a new deficit," wrote Soviet trade in January 1990. “Out of 1,200 basic goods monitored by VNIIKS [Institute of Trade and Demand for Consumer Goods] in 140 cities of the country, only 200 trade relatively smoothly.”

In conditions of less and less satisfied demand, the population periodically rushed to buy up the most common products. So in 1988 in Kiev it happened with sugar, which was literally swept off the shelves. The authorities had to restrict its sale. “We have introduced coupons for sugar in Kiev,” recalls Anatoly Statinov, the last Minister of Trade of the Ukrainian SSR. “Because there was such a rush of demand in the city that stores sold up to three months of sugar a month”.

But neither coupons nor other measures have solved the problem of the growing deficit. Only the abandonment of the socialist planning system and the transition to the marketplace very quickly filled the store shelves with the most different goods... But this has nothing to do with Soviet trade.

The economic and political crisis that gripped the country under "war communism" forced the political leadership to seek a way out of them. The transition from "War Communism" to the "New Economic Policy" (NEP) was proclaimed by the 10th Congress of the Russian Communist Party in March 1921.

The initial idea of the transition was formulated in the works of V.I. Lenin's 1921-1923 years: the ultimate goal remains the same - socialism, but the position of Russia after the civil war dictates the need to resort to the "reformist" method of action in the fundamental issues of economic construction.

The main measures carried out within the framework of the NEP were that the food appropriation system was replaced by a food tax, free trade was legalized, and private individuals were given the right to engage in handicrafts and open industrial enterprises with up to a hundred workers. Small nationalized enterprises were returned to their former owners.

In 1922, the right to lease land and the use of hired labor was recognized, the system was canceled labor services and labor mobilizations. In-kind wages were replaced by cash wages, a new state bank was established and the banking system was restored.

The NEP led to a rapid economic revival. The peasants' economic interest in the production of agricultural products made it possible to quickly saturate the market with food and overcome the consequences of the famine years of "war communism".

However, already at an early stage of the NEP (1921-1923), recognition of the role of the market was combined with measures to abolish it. Official propaganda in every possible way persecuted the private trader, the image of the “Nepman” as an exploiter, a class enemy was formed in the public consciousness. Since the mid-1920s, measures to curb the development of the NEP were replaced by a course towards its curtailment. And on December 27, 1929, in a speech at a conference of Marxist historians, Stalin said: “If we adhere to the NEP, this is because it serves the cause of socialism. And when it ceases to serve the cause of socialism, we will throw the new economic policy to hell. "

And they dropped it: on October 11, 1931, private trade was abolished (except for the collective farm markets). All private shops were nationalized. In the course of the liquidation, all the property of the kulak peasants was confiscated, they were exiled to Siberia, and the urban "Nepmen", as well as their family members, were deprived of their political rights ("disenfranchised"); many were prosecuted.

But the official ban could not finally squeeze out non-state trade from public life... The shadow economy remained a characteristic feature of Soviet reality for a long time.

Retail trade in the USSR

In the first years of Soviet power, the problem of organizing food supplies for the working people was especially acute. The first measures of the Soviet state were the introduction of workers' control over production and distribution, the creation of the People's Commissariat for Food (People's Commissariat for Food) on October 26 (November 8) 1917 to ensure a centralized supply of goods to the population and to organize the procurement of agricultural products. In May - June 1918, due to the aggravation of supply difficulties, emergency measures were taken to resolve the food issue. The "Decree on the Food Dictatorship" was adopted, which gave the People's Commissar of Food extraordinary powers to fight the village bourgeoisie, who sheltered bread and speculated in it; decrees on the reorganization of the People's Commissariat for Food and its local bodies and on the organization of committees of the village poor (kombedov). Much attention was paid to consumer cooperation who was involved in trade service the entire population. In 1918, a state monopoly was established on the trade in the most important consumer goods (bread, salt, sugar, fabrics, etc.), and a ban on private trade was introduced. Trading networks and wholesale warehouses were transferred to the People's Commissariat of Education and its local bodies. These measures undermined the economic positions of the capitalist elements, the struggle against speculation intensified, and opportunities were created to improve the supply of the working people. During the Civil War and foreign intervention of 1918-20. a centralized rationed distribution of consumer goods was established (that is, in fact, the “rationing system” introduced for the first time by the Provisional Government in 1917 was revived). The main form of procurement of agricultural products was the "food distribution" introduced in 1919, which made it possible to concentrate in the hands of the state the necessary resources to supply workers in industrial centers and the army.

With the transition to the New Economic Policy (NEP) in 1921, “surplus appropriation” was replaced by a food tax, small private trade was again allowed, but subject to strict control by the relevant government agencies. With its revival, the need for a card system has disappeared. Importance and high economic efficiency private small trade is proved by the fact that, as of 1924, the private sector owned 88% of the retail trade, its share in the retail turnover was 53%. Organization of internal trade and regulation of market relations on a scale of all National economy The Soviet state began with wholesale trade... Its governing bodies were engaged in the sale of products of large-scale industry: in 1922, the creation of special apparatus, industry syndicates and others state organizations(commodity exchanges, fairs, etc.). Cooperative trade also played an important role in the wholesale trade during this period. With the strengthening of socialist forms of economy in the country's economy, the development of state and cooperative trade, private intermediaries were ousted, first of all from wholesale and then from retail trade. This was facilitated by the government's policy of taxes, tariffs, loans, price reductions, financial assistance to cooperatives and other economic measures.

The transition to industrialization, urban population growth and cash income significantly increased the demand for goods, and small-scale Agriculture could not provide a rapid increase in the production of food and industrial raw materials. This necessitated the transition in 1928 to the rationed supply of the population with basic goods by cards. As government commodity resources increased, "commercial" trade was introduced at higher prices. Along with the development of cooperative trade, state retail trade grew. Since 1928, the creation of "closed" distributors began, supplying goods to workers and employees, enterprises "attached" to them, and in 1932 they were replaced by labor supply departments (ORS). Collective farm trade was allowed, not planned by the state, where prices were set under the influence of supply and demand. As a result of the increase in commodity resources and the development of trade in 1935, the rationing system was finally canceled and a free open trade... In 1935-1941 uniform state retail prices were introduced; the trade apparatus was reorganized. The enterprises of the ORCs and the cooperative trade network in the cities were transferred to state trade organizations. The main sphere of activity of consumer cooperatives has become the development of trade in the countryside. The volume of retail turnover of state and cooperative trade in 1928-40 increased by 2.3 times; number of retailers and Catering increased from 170 thousand to 495 thousand. The turnover of public catering enterprises in 1940 amounted to 13% of the total turnover of state and cooperative trade. The share of socialized forms of trade in the total volume of retail trade increased.

During the Great Patriotic War the system of state rationed supply covered up to 77 million people. Specific gravity catering in retail turnover has almost doubled. On industrial enterprises ORCs were re-organized. All the years of the war, ration prices for basic food and industrial goods remained at the pre-war level. At the beginning of the war, prices on the collective farm markets rose, but already in 1944 their level dropped noticeably due to the "commercial" trade in food and industrial goods. Significantly reduced in 1942 (compared to 1940), retail turnover has increased continuously since 1943, and by 1945 it had reached the level of 200%. At the same time, in the eastern regions, trade grew faster than in the country as a whole.

Despite the enormous difficulties caused by the war, open trade was established at the end of 1947. An important role in this was played by the preparation of the appropriate technical base, restoration and expansion of fixed assets of domestic trade, selection and training of sales personnel. By 1950, centralized retail chains completely recovered, and the trade turnover exceeded the pre-war level (the 1950 figure was 107% of the 1940 level).

Thus, the main specific feature of the Soviet store retail trade can be called its complete subordination to centralized state structures. The process of centralization of trade began in the USSR in the second half of the 1920s, immediately after the winding down of the New Economic Policy. As a result, the share of the private sector in retail first dropped from 50% in 1924 to 30% in 1927. And in 1932, private trade was completely prohibited by law. The same fate befell the cooperative trade sector: if in the same 1932 its share, against the background of a decrease in the number of private traders, increased to almost 60% of the total trade turnover, then by 1940 this figure barely reached 25%.

The general director of dace group llc smbat harutyunyan, the prison trade house

The general director of dace group llc smbat harutyunyan, the prison trade house Yakunin left, Rabinovich stayed

Yakunin left, Rabinovich stayed Rabinovich mikhail daniilovich

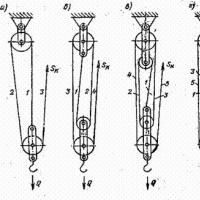

Rabinovich mikhail daniilovich Lifting loads without special equipment - how to calculate and make a chain hoist with your own hands

Lifting loads without special equipment - how to calculate and make a chain hoist with your own hands New details about Dimona's "charity" empire

New details about Dimona's "charity" empire Principal Buyer

Principal Buyer Edward cypherin biography. New Russian. How Eduard Shifrin, having earned $ 1 billion from Ukrainian steel, got involved in development in Russia. Eduard Shifrin and withdrawal of money

Edward cypherin biography. New Russian. How Eduard Shifrin, having earned $ 1 billion from Ukrainian steel, got involved in development in Russia. Eduard Shifrin and withdrawal of money